Calixa Lavallée: Father of Canada’s National Anthem and Lafayette of American music

A Patriots Day Memorial

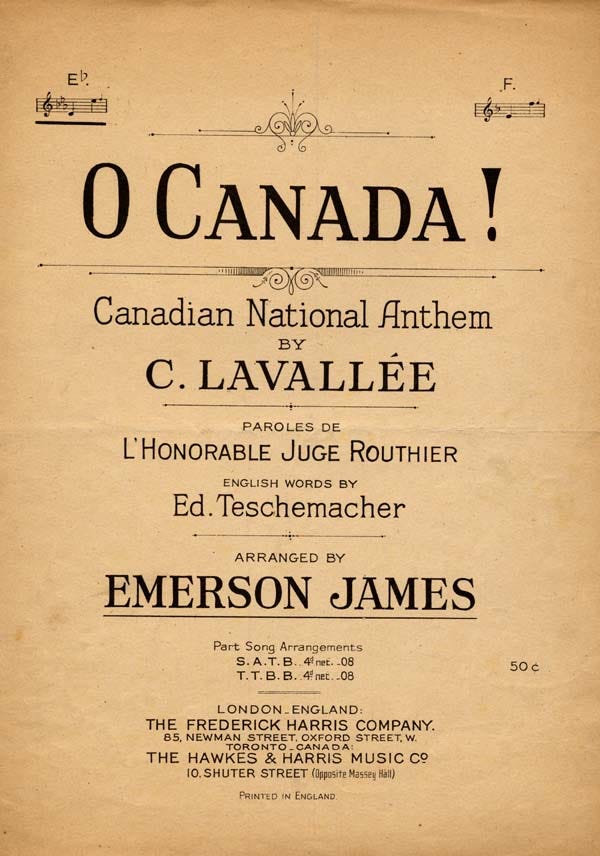

Many may have heard of the name Calixa Lavallée as the composer of the song “Ô Canada” which officially became the Canadian National anthem one hundred years after it was first produced in 1880.

Many know of the name Marquis de Lafayette as the young French nobleman, who changed the course of the American Revolution and devoted his life to the creation of republican institutions both in America and around the globe.

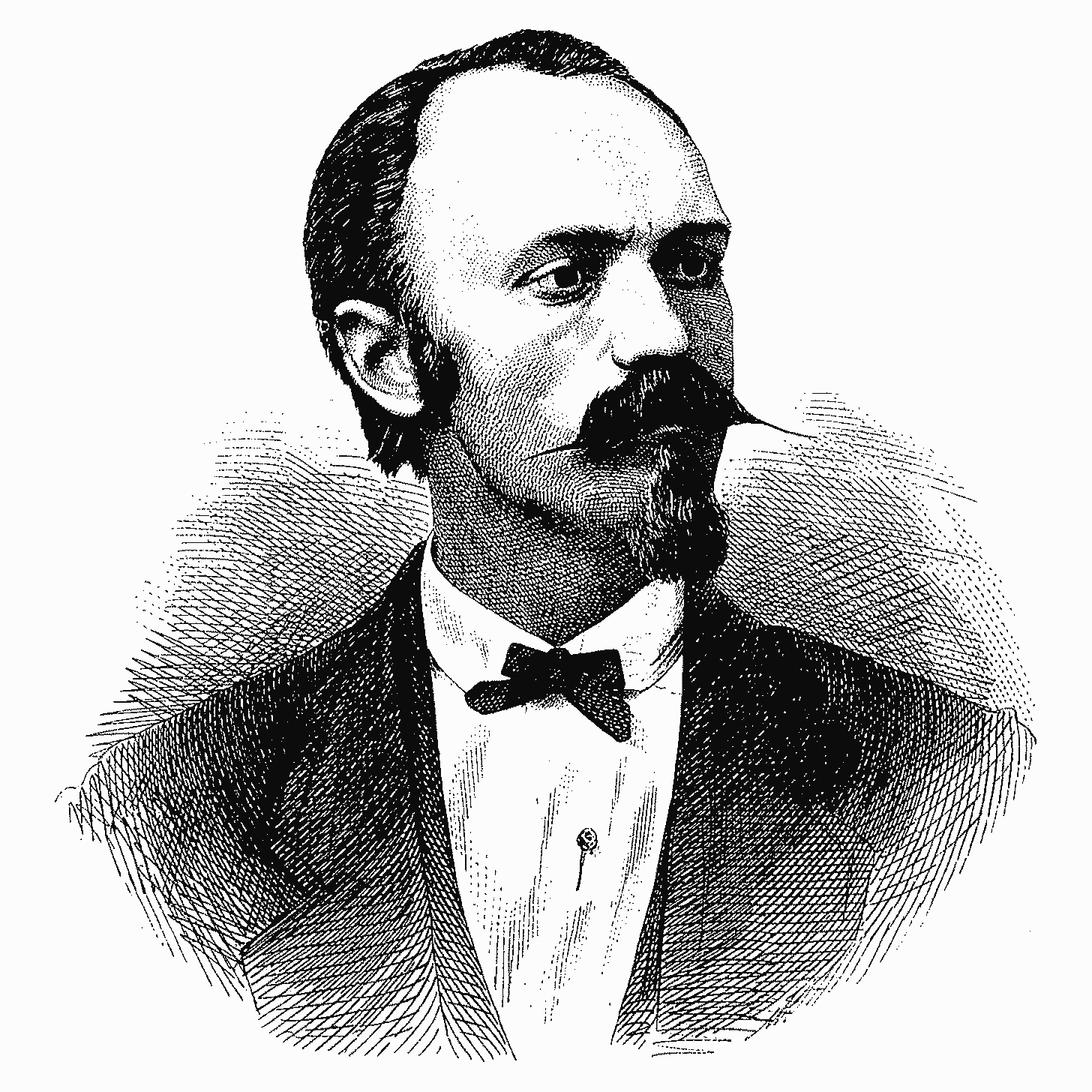

However, few people know that Canada’s Calixa Lavallée (1842-1891), whose life was cut short at the age of 48 was known across America as the “Lafayette of American music”.

Recruited from his home in Saint-Hyacinthe to the elite of the cultural music scene by the Institut Canadien which spread beach heads across all of Quebec throughout the mid-19th century Calixa soon found himself working in Montreal and studying under the mentorship of the great French composer Charles Wugk Sabatier who composed the famous patriotic song “Le Drapeau de Carillon”. In order to earn a living, Calixa began touring America as a director and performer of minstrel shows just as the first shots on Fort Sumter ushered in the Civil War in April of 1861.

The Civil War Veteran Fights Two Confederacies (south and north)

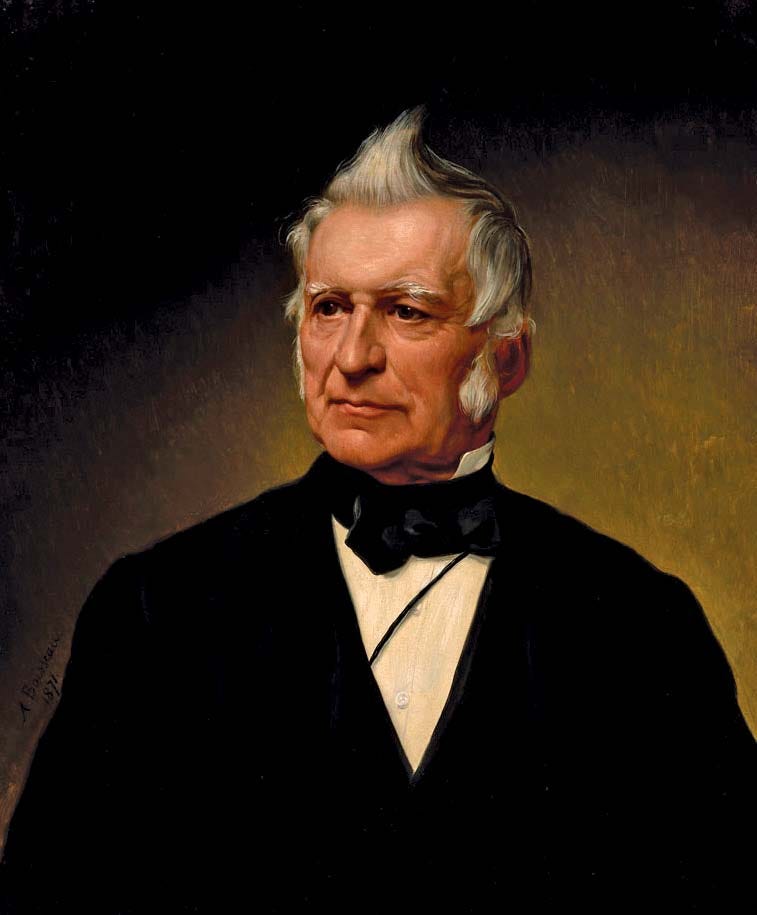

A devoted republican inspired by the traditions of Louis-Joseph Papineau, leader of the failed Lower Canada Rebellions against the British in 1837-1838, Calixa was quick to join the Union Army in the 4th Rhode Island regiment fighting in one of the bloodiest Civil War battles of Antietam in Maryland in September 1862 where his wounds ended his time in the military. Papineau had himself created the Institut Canadien in 1844 in order to provide an aesthetical and scientific education to the masses of the Quebec population who did not have the adequate cultural development to properly undertake a complex revolution as he had dreamed years earlier. Papineau’s nephew Louis-Antoine Dessaulles was the President of the Montreal branch of the Institut Canadien and former seigneur and mayor of Saint-Hyacinthe who knew Lavallée’s family well and likely played a role in the early part of the young man’s career.

Lavallee in his union uniform 1862

Struck with the realization that Lincoln’s victory would finally create international conditions favourable to Canada’s liberation from the British Empire, Lavallée returned home to Montreal in 1863 in order to help guide the young nation towards becoming a republic free of hereditary institutions.

Lavallée quickly found himself allied with a powerful network of young nationalists then dubbed “Les Rouges” led by L.-O. David, Médéric Lanctôt (his childhood friend and founder of La Presse), and a young lawyer named Wilfrid Laurier (later to become Prime Minister of Canada from 1896-1911). These republican networks quickly set up a newspaper known as L’Union national which was devoted to overthrowing a London-steered plot to create a British confederate beachhead in the Americas after it had become apparent that London’s “other” confederate operation in the slave owning south was about to fail. That plot came to be called the “British North America Act” and was first drafted after a booze-drenched conference in Charlottetown Nova Scotia in September 1864.

Before it was ratified in London on July 1 1867, Lavallée’s entourage led a two-fold combat against this anti-republican program which they saw as a perversion of human nature (as it embedded hereditary rights and powers into the very constitution of the new nation).

Louis-Joseph Papineau

The Union National and La Presse newspapers run by Lavallée’s friends held a clearly defined position that the only two acceptable pathways to the future for Lower Canada was 1) Full independence from the British Empire or 2) Annexation to Lincoln’s America.

All members of this group recognized the dangerous fallacy of composition that would be unleashed should a nation be created on British Imperial foundations and administered by Privy Council networks loyal to a hereditary power structure.

The Battle Against the Ultramontane Church

While polemicizing against Confederation, the L’Union national newspaper and the Institut Canadien de Montéal conducted a second line of battle by advocating a separation of Church and State. This put them into conflict with the Ultramontane Church whose tyrannical leadership under Montreal’s Bishop Bourget demanded that the population of Quebec show their faith to God by remaining as ignorant as Adam and Eve were before spoiling their morality by eating from the tree of knowledge. It was this commitment to keeping the population in a peasant dream state that the corrupt church then found itself so closely aligned with the highest echelons of the British Empire.

Bishop Ignace Bourget

When Bishop Bourget excommunicated Joseph Guibord due to his membership in the Institute canadien, as punishment for the institut’s refusal to ban books from the library which were placed on the Church’s black list, many supporters quickly abandoned the fight out of fear and the Institut canadien began crumbling.

The L’Union national newspaper collapsed when the British North America Act passed into law in 1867 whereby the paper lost its raison d’etre.

In spite of these setbacks, the fight was not over for Calixa.

Taking Lazard Carnot’s famous statement seriously that “it is better to have republicans without a republic than a republic without republicans”, and recognizing that the conditions for republicanism was the moral, and intellectual cultivation of the personality in alignment with the ideals of Benjamin Franklin and Friedrich Schiller, Lavallée devoted the remainder of his life to creating durable cultural institutions that could organize, develop and deploy the creative powers of the population so that future generations could succeed where his generation failed.

To undertake this task, Calixa had recognized that he must first cultivate his own artistic powers to a much higher degree. After working as an exile in America for several years becoming the superintendent of the Grand Opera of New York (as an appointee of his friend and soon-to-be assassinated musical patron Jim Fisk in 1872), Lavallée briefly returned back to Montreal bursting with passion to create a conservatory of Quebec and a durable classical musical culture capable of producing native geniuses, and Canadian compositions.

Studying in France from 1873-1875 under the tutelage of the great pedagogue François Marmontel, Lavallée’s powers of performance and composition grew to new heights and several original works were produced including the Papillon, Souvenirs de Tolède, La Grande Marche and the Fatherland Overture.

The Fight for a Canadian Conservatory

Having returned to Montreal in 1875 Calixa gave everything to his mission and made alliances with every person of influence he could come into contact with in order to gain support for his Canadian Conservatory. To pay his bills, he tutored prolifically, arranged countless concerts – often with the Montreal-based Mechanics Institute and worked as organist in many churches across Quebec. In one instance, the new ultramontane Bishop of Montreal Édouard-Charles Fabre passed a decree banning mixed choruses in all diocese churches causing Lavallée to resign, taking the Saint-Jacques Church choir with him.

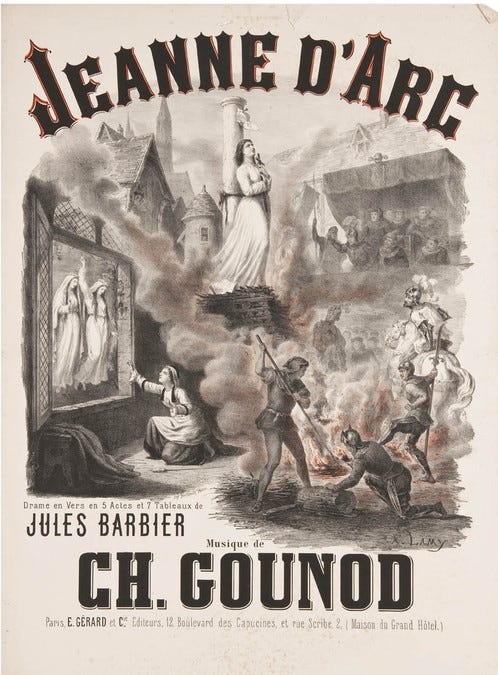

In response to this attack on culture, Lavallée decided to fight back by organizing his choir to perform Gounod’s Jeanne d’Arc. Jeanne was recognized as a Promethean symbol of republicanism across the world and a figure who saved her nation in a time when all hope for freedom was lost. For this, d’Arc was burned at the stake by an unholy alliance between the Catholic Church and the British Aristocracy who ran a mock trial declaring her to be an agent of the devil.

In the wake of the electric success of the performances of Jeanne d’Arc, Lavallée became president of the prestigious Académie de Musique de Québec (AMQ). The AMQ was founded in 1868 as an instrument to administer musical examinations and conduct talent searches as part of the drive to create a national musical culture. Once made President in June 1876, Lavallée devoted his every free moment to the AMQ. After a successful 1877 session of the AMQ music competition which included performances of the greatest young talents from around Québec, an article published in Le National and attributed to Lavallée read: “Yesterday’s results have clearly shown us that there could be a music school just as there is one for the fine arts and that this school should be funded in a manner that best encourages the continuation of work and the spread of this the most noble and beautiful art, the one that best raises the soul toward its creator.”

Sadly by June 19, 1878 Lavallée was saddened to receive news that his petition to create a conservatory submitted a year earlier had crept through the bureaucracy and became a Bill only to be struck down on procedural grounds. The Québec-city newspaper L’Événement reported on this short-sighted decision saying: “Analyzing the public feeling regarding serious musical institutions, one soon discovers a profound ignorance of the importance of music, of the necessity of institutions organized appropriately in its interest and of its potential as the co-efficient of a superior civilization. This ignorance is found to some extent everywhere, among the governed and the governors, but is most serious among the governors.”

A Change of Strategy

At this point, Lavallée changed his strategy to focus on the failure of the governors. Rather than focus all of his attention to “bottom up” organizing of the population while hoping the elite would respond to the call of the times, Calixa moved to Québec City in 1878 in order to be closer to the Assemblée nationale and the political class whose favor he needed for his plan to succeed. Establishing himself in Quebec City, Lavallée quickly became a founding member of an interesting republican group of artists, poets, musicians and statesmen called “Le Club des 21” (whose name was derived by the 21 member limit). The group’s president was the diplomat musician José Antonio De Lavalle Romero-Montezumaa (aka: the Count of Premio-Real) who served as the Spanish Consul to Quebec.

Calixa worked hard to procure favor and friendship wherever it could be found, devoting an enormous amount of energy to the Lieutenant Governor of Quebec and the Governor General the Marquis of Lornes (John Douglas Campbell) who had been appointed to represent the Crown as the new head of state of Canada that year. Many of his compositions featured dedications to members of the Anglo-Canadian elite during this time, which Lavallée has been heavily criticized for over the years. However it is only by understanding his strategic plan to by-pass the bureaucratic channels of government that we can appreciate what he was doing.

Lavallée produced a spectacular cantata for the new Governor General in 1878 and performed a selection of it in Ottawa’s Rideau Hall where it was warmly received by the Marquis and his wife who befriended Calixa, talking with him throughout the night.

When the Marquis finally came to Québec City in June 1879, Lavallée gave the full performance of the Cantata for the first time featuring 150 singers and 60 instrumentalists. Never one to break from his republican passions, the poetry selected for the cantata included a military chorus celebrating the French victory over the English. The translated text is worth citing here:

First Soldier

The drum beats, the bugle rings,

Here, the call of the regiment;

On the ramparts the cannon thunders

Let’s go, companions, forward!

Second Soldier

Let us leave, let us show our banners,

Oriflammes, floats on the wind!

And you, old flag of our fathers,

Unfold your triumphant pleats

Chorus

Ring, battle bugles

Cannons, thunder towards the skies!

Awaken from our walls

The glorious echoes of the past!

And, you magnanimous warriors

That sleep beneath laurels,

Rise, sublime heroes,

Show your proud foreheads!

To the walls of the cathedral

Unhook the white flag;

In the triumphant march

Come to take your rank!

Finale

O days of glorious combat

Where rang the warlike horn!

O all of you, brave soldiers

That sleep under the same rock!

Sun that formerly illuminated

So of great battles

Night discreetly reveals

So many bloody funerals!

The blood everywhere is obliterated:

Gather together our glory,

From great names of our past

Let us sing together our history!

The lyrics were so scandalous that it was decided to not publish the lyrics at the event.

While the Marquis did not indicate any open displeasure towards Calixa, neither he nor any of the elites whom Calixa attempted to win over to the cause supported the conservatory project. Although a hope briefly arose in October 1879, when Joseph-Adolphe Chapleau (a member of Calixa’s Club de 21) became premier of Quebec, it was soon squashed as Chapleau made no moves in support of his friend.

O Canada is Born

By June 1880, the Congrès Catholique Canadiens-français had commissioned Lavallée to compose a national song for Canada. Although many English speakers considered “God Save the Queen” and “the Maple Leaf Forever” as unofficial anthems, these were not pieces that the French could relate to and something more universal was required. Calixa went straight to work.

Working alongside conservative judge and poet A.B. Routhier who authored the original words to the anthem, Lavallée had requested that the poet wait until the music was first composed before choosing the lyrics. As Lavallée had recently conducted a series of performances of works by Mozart such the Twelfth Mass and operas by Verdi, and Rossini, the Magic Flute (the famous “masonic” opera) was likely fresh in his mind when he composed the music to what became known as “Ô Canada”.

Upon listening to the first two measures of Act two (the March of the Priests), the borrowed melody is striking and leaves very little doubt that Mozart was the inspiration for the anthem.

The fact that the ceremony at which the anthem was scheduled to be performed was to follow a Mass given by the ultramontane Archbishop of Quebec accompanied by 500 priests may have been tied to Lavallée’s choice of Mozart’s march of the priests under the leadership of Zarastro as his inspiration. When one realizes that the priests in Mozart’s opera called for an obedience to a Natural Law that rises above man’s religions, it becomes no surprise that Lavallée’s composition was pulled from its scheduled debut that day. Whatever the case, it was performed to a smaller audience at a national banquet that evening and once more in the morning to very positive effect. In spite of its positive reception, no signs emerged that his dream of a conservatory had come any closer to reality.

In the following weeks, Lavallée received an opportunity to plant his dream in more fertile soil as an invitation to leave Canada for the USA arose. This was an opportunity he did not pass up and in the heat of the night, without any fanfare, Lavallée departed for America.

In Hartford Connecticut, Lavallée wrote to a friend in Quebec describing the spread of slander and gossip against the composer: “When one returns here, one realizes the insignificance of the ideas of our poor country… I have complete confidence in this trip as well as in others, and besides, an artist is not meant to rot in an obscure place and especially in an even more obscure country.”[1]

Lavallée’s friend could see that the composer was frustrated and exhausted after five years of efforts to create a conservatory had found no support. He made an appeal to the Quebec government knowing that it was likely that Lavallée would not return if nothing were done: “In the aftermath of Mr. Lavallée’s wonderful results, the government that has already generously assisted in the organization of this lovely musical event must also help such a talent to develop and produce other works that will contribute to the artistic progress and glory of Canada. We only need to found a music conservatory where our talented young people- which we certainly do not lack- may take shape, and place at the head of that institution a man of unparalleled calibre such as Mr. Lavallée.”[2]

As those wise words fell on deaf ears, Calixa decided to settle roots in America, and establishing himself in Massachusetts. It was here that he chose to devote all of his energy to create an American Conservatory where the Canadian Conservatory project failed. In his new republican home, his efforts would prove infinitely more successful.

The Lafayette of American Music

After composing his first opera, The Widow, to great success, Calixa attempted a second, more radical intervention into the American culture with a satirical comic opera called The Indian Question Settled At Last which featured the real life events surrounding Indian Chief Sitting Bull as a Zorastro-like wise figure who guided foolish soldiers, missionaries and natives into a state of wisdom by encouraging everyone to part with their prejudices and awaken love for each other with various natives and whites falling in love and living in harmony. This second play was deemed too controversial for the stage and it was never performed whereby Calixa decided to leave operas behind him and focus on a new pathway which brought him into contact with the Music Teachers National Association (MTNA) in Rhode Island in 1883.

By the end of this 1883 meeting Calixa recommended to the MTNA President E.M.B. Bowman, the unthinkable idea of organizing a concert made up of American composers the following year. Lavallée’s biographer Christopher Thompson wrote that “it seems that playing a program of music composed by one’s U.S. contemporaries was something no one had considered doing.”

The following year, the fruits of Lavallée’s efforts paid off as a 100% American repertoire was performed for the first time in history on July 3, 1884 at Case Hall in Cleveland, Ohio. In the wake of the incredible success of this concert, a letter to the Senate and House of Representatives by MTNA members led to the passage of the first copyright legislation for music into law. In gratitude for initiating this bold new movement, Calixa was named Vice President of the MTNA. Reporting on the concert, Folio magazine stated that Lavallée’s concert had inaugurated “a new departure in the musical history of the country”.

On July 4 1884, the MTNA announced the creation of the American College of Musicians (ACM) with the goal of examining music teachers under various categories of music (voice, piano, organ, theory) and offering various grades of proficiency (master, fellow and certificate of competency). Lavallée gave a stirring speech at the event and he was elected to head the program committee. The College fell under heavy attack by many of the “musical Brahmins” of New England who controlled the musical scene as the self-ordained elite. The primary enemy of the ACM was Eben Toujee, a co-founder of the MTNA who feared that the new institution broke the monopoly enjoyed by the New England Conservatory of which he was president.

Lavallée and Thurber Lead the Movement for a New School of American Music

With Lavallée now firmly driving this new movement, visionary art patron Jeanette Thurber joined the cause going on to found the American Conservatory in 1885. Lavallée’s biographer Brian C. Thompson noted the dramatic growth of the MTNA once Thurber offered her support: “With the financial support of the arts patron Jeannette Thurber, the MTNA raised its profile to a new level with its 1885 summer meeting in New York.”

Jeanette Thurber

During the 1886-1887 meeting, President S.N Penfield endorsed Lavallée’s election to the presidency of the institution saying “You may refer to last year, when American compositions were given in a very worthy manner at the Academy of Music in New York, with a large orchestra and chorus, under the auspices of the President and officers of that year. But what led up to that? One modest piano recital of the year before (applause) by a gentleman who staked his reputation upon it. That, in one sense, was the commencement of this policy of the Music Teachers’ National Association, which has now grown to these dimensions. I have the honor to present, as your candidate for the Presidency in the ensuing year, the gentleman who gave that recital, Mr. Calixa Lavallée, of Boston.”

Toasting to the prospects of the new movement, composer Wilson G. Smith said on March 15, 1886: “To Mr. Lavallée (a foreigner, too, be it said to the shame of some of our native artists) belongs the honor of inaugurating the present movement, on behalf of American composers and their works. The history of American art will accord to him this distinction”.

In gratitude for being elected President, Lavallée said that he would “put his heart, soul and all his energy, into the service of American music.”

True to his word, Calixa was known for working 16-18 hours per day, teaching, organizing concerts, programs, composing, fundraising and managing administrative affairs of the MTNA, often out of his own pocket. He worked closely with conductor Frank Van der Stucken, and also E.M. Bowman and Carlyle Petersilea to advance the careers of such composers as George Chadwick, John Knowles Paine, Arthur Foote, Wilson Smith, Ernst Jonas and Emil Liebling among many others.

Although he was the acting President of the MTNA at the 1889 meeting in Philadelphia and re-elected to chair the Program committee for the 1892 meeting at the Columbia Exposition, Calixa had pushed himself too far and succumbed to tuberculosis dying on January 21, 1891 at the age of 48.

At the 1892 meeting’s Presidential address, J.B. Hahn spoke of the new movement and the role played by Lavallée:

“It was in this city- yes, in this very hall, eight years ago, that Calixa Lavallée sounded the key-note of a movement whose reverberations found a re-echoing and a responsive sentiment throughout the length and breath of the land. Many here today will readily remember the occasion- a modest, unpretentious pianoforte recital, with the distinguishing characteristic that it was the first complete programme of American compositions ever presented… For his patriotism, his courage, his judicious selection which led to victory and the leadership he then assumed, all honor to our late associate and ex-President, Calixa Lavallée, the Lafayette of our American musicians.”

Just nine months before his death, Calixa gave an interview to the Boston Herald describing his inspired hope and vision of the new epoch in American composition that he had helped to unleash:

“Somebody must sacrifice themselves for the cause. When I read the dispatch from Washington two or three weeks ago about the successful concert of American composers given at that city I was delighted. I little dreamed six years ago that the incipient effort I made in that direction would find its reward so soon. No, American music has come to stay and the sooner the American public realizes the fact the better for the cause and all parties concerned. Of course, we are working through a transition, which is the fate of every new country, and it may take some years yet before we acquire a national color to our music: but who knows how soon a genius may come to us to crown our labors.”

Epilogue

1892 was an auspicious year for the movement. Although Lavallée did not live long enough to see his prophecy unfold, this was the year that Jeanette Thurber brought another foreign musical genius to America in order to guide the America through its transition in the discovery of “a national color”.

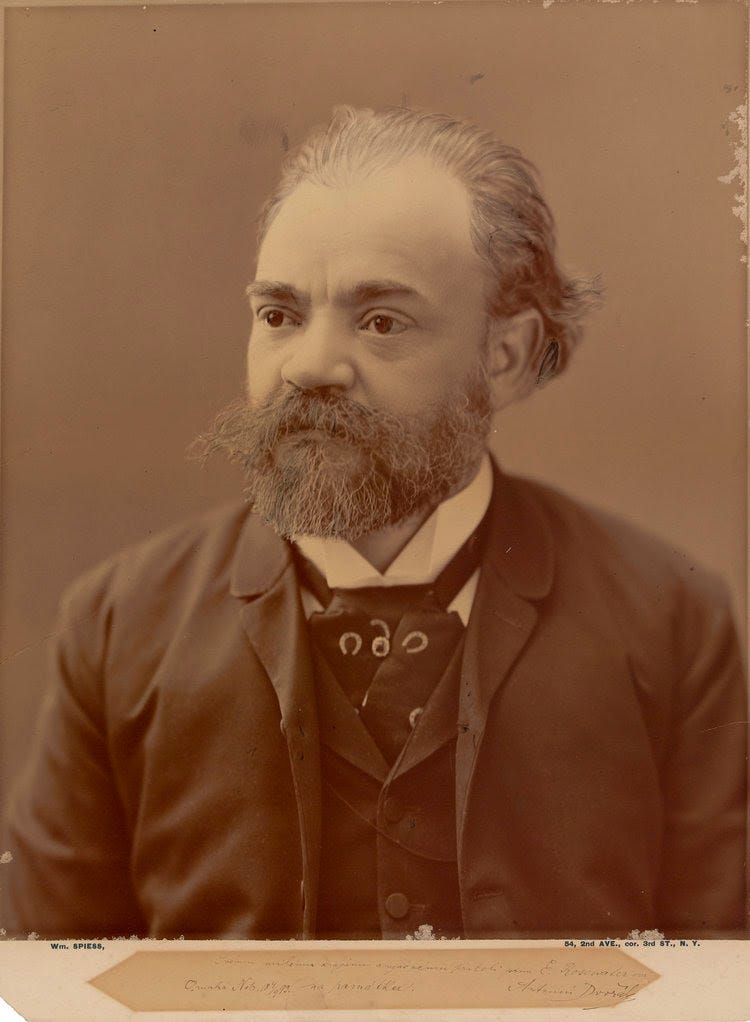

Antonín Dvořák

Leading Hungarian-born composer Antonín Dvořák arrived in New York in September 1892 and set to work to pick up the baton where Lavallée had left it in 1891, becoming the leading figure in Thurber’s National Conservatory of America and creating a new school of American music generated from his intense studies of Native American, and African-American melodies. Dvořák gave an interview to the NY Herald on May 23, 1893 saying:

“I am now satisfied that the future music of this country must be based on what are called the negro melodies. This must be the foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States…These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are American.”

Dvorak’s work resulted in his 1893 New World Symphony, and a new generation of African American composers and musicians under the leadership of Harry Burleigh, the Fisk Jubillee singers and many more.

Footnotes

[1] Brian C. Thompson, Anthems and Minstrel Shows: The Life and Times of Calixa Lavallee, McGill-Queens University Press 2015, P.228

[2] Ibid, p. 230

Additional information for researchers: