Turkey's Existential Choice: BRI or Bust

By Matthew Ehret [Originally published on the Cradle]

Two destinies pull on Southwest Asia from two opposing visions of the future.

Where the devotees of the Rules Based Order laid out by Zbigniew Brzezinski 40 years ago strive to revive the dystopic nightmare of sectarianism and endless wars, a more optimistic program of cooperation and long-term thinking is being ushered in by China’s ever-evolving Belt and Road Initiative.

While many nations have jumped on board this optimistic new paradigm enthusiastic support, others have found themselves precariously straddling both worlds.

Turkey Escapes from the Oven?

Chief among those indecisive nations is the Republic of Turkey, whose leader was given a harsh wake up call on July 15, 2016. It was on this date that Russian intelligence provided Erdogan the edge needed to narrowly avoid a coup launched by followers of CIA-protected cult leader Fetullah Gulen.

The reason why the coup was launched at that time has been subject to much speculation, but the fact that it occurred just two weeks after Erdogan’s letter of apology to Putin went public was likely not a coincidence. The apology in question referred to Turkey’s decision to shoot down a Russian fighter jet flying in Syrian airspace in November 2015 resulting in the death of a soldier and the near-activation of NATO’s collective security pact… and thus WWIII.

Perhaps Turkey, which had been instrumental in providing weapons, and logistical support to ISIS in both Iraq and Syria (via Operation Timber Sycamore) was getting sick of being a tool by western forces who obviously didn’t mind sacrificing the entire Arab world on the alter of a New World Order. Or perhaps Erdogan began seeing a little Saddam Hussein in the mirror.

Whatever the case, since that fateful day, Turkey’s behaviour as a player in Southwest Asia has certainly taken on an improved (although not entirely redeemed) character on a number of levels. Chief among those positive behavioral changes, we have seen Turkey’s participation in he Astana process beginning in 2017, reducing support for nasty regime change tactics in the region, and even purchasing Russia’s S400 medium-long range missile defense systems starting in 2017. The latter systems have angered more than a few western NATO-philes due S400’s tendency to render Anglo-American missile shields impotent and obsolete.

Military cooperation with Russia has also amplified with Erdogan’s September 29 visit to Moscow where the beleaguered Turkish leader pledged to purchase a second tranche of S400 air defense systems, advanced plans to jointly produce submarines, jet engines, warships with Russia while also accelerating the construction of a nuclear reactor built by Rosatom.

That said, old habits die hard, and Turkey has continuously been caught playing in both worlds providing continued support for the terrorist-laden Free Syrian Army and newly repackaged Al Qaeda group Hayat Tahrir Al Sham which uses Idlib as their home base. The leaders of Russia and Syria understand that Turkey bears a fair bit of responsibility for this mess as 60 military bases and observation posts provide protection for these and other militant groups.

The Middle Corridor Potential

On an economic level, Turkey’s ambition to become a gateway between Europe and Asia along the New Silk Road also indicates Erdogan’s resolution to break from his previous commitments to join the sinking ship of the European Union and instead tie Turkey’s future towards the East.

Turkey’s 7500 km Trans Caspian East West Middle Corridor is a beautiful program that runs parallel to the Northern corridor of the BRI connecting China to Europe.

This corridor which began running in November 2019 has the benefit of cutting nearly 2000 km of distance off the active northern corridor and provides an efficient route between China and Europe. The route itself moves goods from the Northeastern Lianyungong Port in China through Xinjiang into Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey and on to Europe via land and sea routes. Erdogan has previously stated that “the Middle Corridor lies at the heart of the BRI” and called to “integrate the Middle Corridor into the BRI”.

Other projects that are subsumed by the Middle Corridor include the $20 billion Istanbul Canal which will be a 45km connection between Black and Marmara Seas (reducing traffic on the Bosporus) as well as the Marmaray undersea railway, Eurasian Tunnel and third Istanbul Bridge.

Without China’s increased involvement, not only will these projects fail, but the Middle Corridor itself would crumble into oblivion. To date, Chinese trade with Turkey has grown from $2 billion in 2002 to $26 billion in 2020, and over 1000 Chinese companies have investment projects throughout the nation. Chinese consortiums have a 65% stake in the 3rd largest port of Turkey.

Shoving Turkey Back in the Oven

These projects have not come without a fight both from forces within Turkey and externally.

Two major Turkish opposition parties have threatened to cancel the Canal Istanbul as a tactic to scare away potential investors both at home and abroad.

Internationally, financial warfare has been unleashed against Turkey’s economy on numerous levels.

Credit ratings agencies have downgraded Turkey to a “high risk” nation, and sanctions have been launched by the US and EU. These acts have contributed to international investors pulling out from Turkish government bonds (collapsing from ¼ of all bonds held by international investors in 2009 to less than 4% today) and depriving the nation of vital productive credit to build infrastructure. These attacks have also resulted in the biggest Turkish banks stating they will not provide any funding to the megaproject.

Despite the fact that Chinese investments into Turkey have increased significantly, western Financial Direct Investments (FDIs) have fallen from $12.18 billion in 2009 to only $6.67 billion in 2021.

Turkey’s Changing Relationship with the Uyghurs

Just as we see with Turkey’s relations with Russia, her desperate need to collaborate with China has resulted the emergence of a saner policy regarding Erdogan’s support for Uyghur extremists. Of the 13 million Chinese Uyghurs, 50,000 live in Turkey, many of whom are part of a larger CIA-funded operation aimed at carving up China.

For many years, Turkey has provided safe haven to groups such as the East Turkmenistan Islamic Movement which cut its teeth fighting alongside ISIS in Syria and Iraq. Operatives affiliated with the National Endowment for Democracy funded World Uyghur Congress based in Germany have also found fertile soil in Turkey.

It was only 2009 that Erdogan publicly denounced China for conducting a genocide on the muslims living in Xinjiang (long before it became cool to do so among western nations). By the 2016 failed coup, things began changing with Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu stating in 2017: “we absolutely will not allow in Turkey any activities targeting or opposing China. Additionally, we will take measures to eliminate any media reports targeting China.”

With many parallels to Turkey’s protection of radical Islamic groups in Idlib, the habit of protecting radical anti-Chinese Uyghur groups has been piece meal. However significant moves have been made by Erdogan demonstrating good faith including the 2017 extradition treaty signed with China (ratified by Beijing though not yet by Ankara), an increased clamp down on Uyghur extremist groups and the decision to re-instate the exclusion order banning World Uyghur Congress president Dolkun Isa from entering Turkey on September 19, 2021.

Might the INSTC Bypass Ankara?

Not only is Turkey desperate to play a role in the Belt and Road Initiative and secure much-needed long term credit from China without which her future will be locked into the hellish fate of the European time bomb, but the growing International North South Transportation Corridor also factors into her calculus.

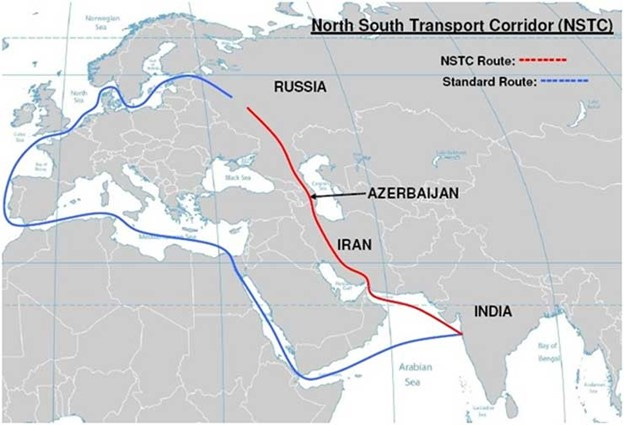

A multimodal corridor stretching across a dozen nations, the INSTC was launched by Russia, India and Iran in 2002 and has been given new life amidst China’s BRI. In recent years, members of the project have grown to also include Azerbaijan, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, Syria, Belarus, Oman and Bulgaria.

While Turkey is a member of the project, there is no guarantee that the megaproject will directly move through her borders at this time. Thus, here too, Erdogan is desperate to stay on good terms with Russia and her allies.

The International North South Transportation Corridor [image: Wikicommons]

The Middle Corridor Loses its Shine

Up until now, Turkey’s inability to break with zero-sum thinking has resulted in leading figures around Erdogan deluding themselves into thinking that Turkey’s Middle Corridor would be the only possible choice China had to move goods through the world island to Europe and North Africa.

This perception was for many years enhanced by the ongoing war across the ISIS-ridden region of Syria and Iraq (and relative isolation of Iran) ensuring that no competing development corridor could be activated.

However, with Tehran’s entry into the Belt and Road Initiative with the recent $400 billion deal with China and its additional full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a new east-west corridor has been born which provides an attractive alternative route to the Middle Corridor.

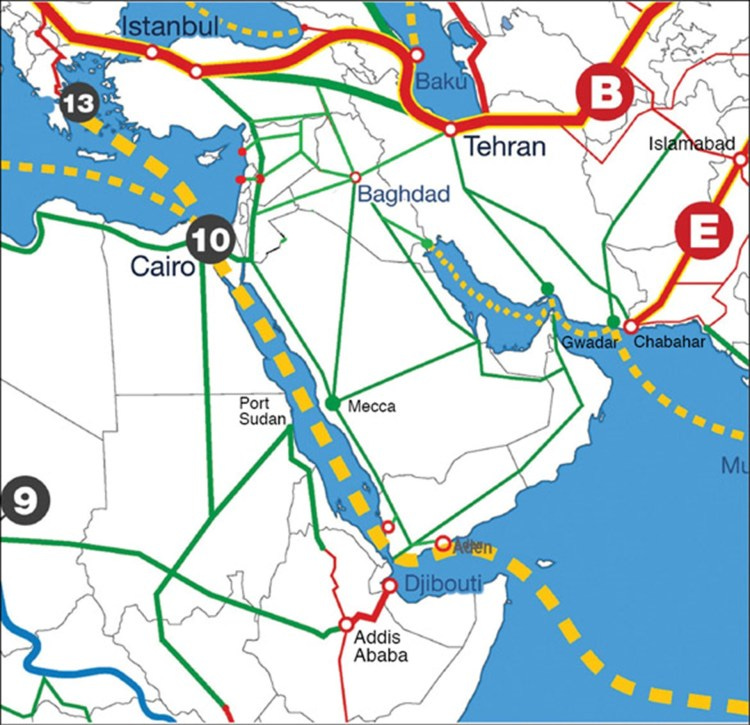

This new branch of the New Silk Road connecting China with Europe via Iran, Iraq and Syria into the Mediterranean through Syria’s port of Latakia provides an incredible opportunity to not only reconstruct the war-torn Southwest Asia but also create a durable field of stability after decades of western manipulation. This new route has the additional attraction of incorporating Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and other Arab states into a new strategic dynamic that connects Eurasia with an African continent desperate for real development. As of this writing, 40 sub-Saharan African nations have signed onto China’s BRI.

The first glimmering light of this new corridor has taken the form of a small but game changing 30 km rail line connecting the border city of Shalamcheh in Iran with Basra in Iraq first unveiled in 2018 and begun this year with its $150 million cost supplied by the semi-private Mostazan Foundation of Iran.

Foreseeing a much larger expansion of this historic connection, Iran’s ambassador to Iraq stated: “Iraq can be connected to China through the railways of Iran and increase its strategic importance in the region… this will be a very big change and Iran’s railways will be connected to Iraq and Syria and to the Mediterranean”.

Ambassador Masjidi was here referring to the Provisional agreement reached among Iran, Iraq and Syria in November 2018 to build a 1570 km railway and highway from the Persian Gulf in Iran to the Latakia Port via Iraq.

Already Iran’s investments into war torn (and sanction torn) Syria have grown immensely with a focus on construction materials with an estimated trade boost between the two nations of $1 billion over the next 12 months.

Indicating the higher development dynamic shaping the Iraq-Iran railway, Iraq’s Prime Minister stated in May 2021 that “negotiations with Iran to build a railway between Basra and Shalamcheh have reached their final stages and we have signed 15 agreements and memorandums of understanding with Jordan and Egypt regarding energy and transportation lines”.

Indeed, both Egypt and Jordan have also looked east seeing the only pathway for durable peace in the form of the New Silk Road. The trio of Egypt, Jordan and Iraq began setting the stage for this Silk Road route with a 2017 energy agreement designed to connect the electricity grids of the three nations and also construct a pipeline from Basra to Aqaba in Jordan followed by a larger extension to Egypt.

A Broad array of development corridors await the African and Arab worlds if the current Iraq-Syria-Iran triad can avoid being destabilized. The image above features several possibilities [Schiller Institute]

Iraq and the New Silk Road

In December 2020, Iraq and Egypt agreed on an important oil for reconstruction deal along the lines of a similar program activated earlier by former Iraqi Prime Minister Adil Abdul Mahdi and his Chinese counterparts in September 2019.

Standing beside Xi Jinping in September 2019, former PM Mahdi stated: “Iraq has gone through war and civil strife and is grateful to China for its valuable support… Iraq is willing to work in the ‘One Belt One Road’ framework”. President Xi then said: “China would like, from a new starting point together with Iraq, to push for the China-Iraq Strategic Partnership”.

Sadly this project was seriously downgraded when Mahdi stepped down in May 2020 and although PM Mustafa Al-Kadhimi has begun to repair Chinese relations, Iraq has not yet returned to the level of cooperation reached by the previous government.

Up until this moment, the only powerful nation that has shown any genuine concern for Iraq’s reconstruction has been China.

Despite the trillions of dollars wasted by the United States in bombing the country back to the stone age, not a single energy project was built by US dollars since the invasion. In fact, the only power plant constructed after 2003 has been the Chinese-built 2450 mW thermal plant in Wassit which supplies 20% of Iraq’s electricity. Iraq requires at least 19 GW of electricity in order to supply its basic needs after years of western bombardments strategically targeting its vital infrastructure at the cost of millions of innocent lives.

To this day, hardly any manufacturing exists domestically with 97% of Iraq’s needs purchased from abroad (and entirely with oil revenue). If this dire situation is to be reversed, then China’s oil-for-construction plan must be brought fully back online.

The kernel of this plan involves a special fund which will accumulate sales of discounted Iraqi oil to China until a $1.5 billion threshold is reached. Once that moment happens, Chinese state banks have agreed to add an additional $8.5 billion bringing the fund to $10 billion to be used on a full reconstruction program driven by roads, rail, water treatment, and energy grids as well soft infrastructure like schools and healthcare. Where the western economic models have tended to keep nations underdeveloped by emphasizing raw material extraction with no long-term investments that benefit the people, create manufacturing or increase the powers of labor, the Chinese-model is entirely different, focusing instead on creating full spectrum economies. Where one is Hobbesian, zero sum and closed system, the superior model is non-zero sum, win-win and open.

IF Turkey can find the strength to liberate herself fully from the obsolete logic of zero sum geopolitics, then a bright future will certainly arise for the entirety of Southwest and Central Asia.

There is no reason to believe that the Middle Corridor will be in any way harmed by the success of an Iran-Iraq-Syrian Silk Road corridor, nor its African extensions. By encouraging peace, large scale infrastructure, full spectrum economic systems more abundance is created in the long term leaving every participant wealthier and safer in the process.

Matthew Ehret is the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Patriot Review , and Senior Fellow at the American University in Moscow. He is author of the‘Untold History of Canada’ book series and Clash of the Two Americas. In 2019 he co-founded the Montreal-based Rising Tide Foundation . Consider helping this process by making a donation to the RTF or becoming a Patreon supporter to the Canadian Patriot Review