Edgar Poe as Cultural Warrior Part 2

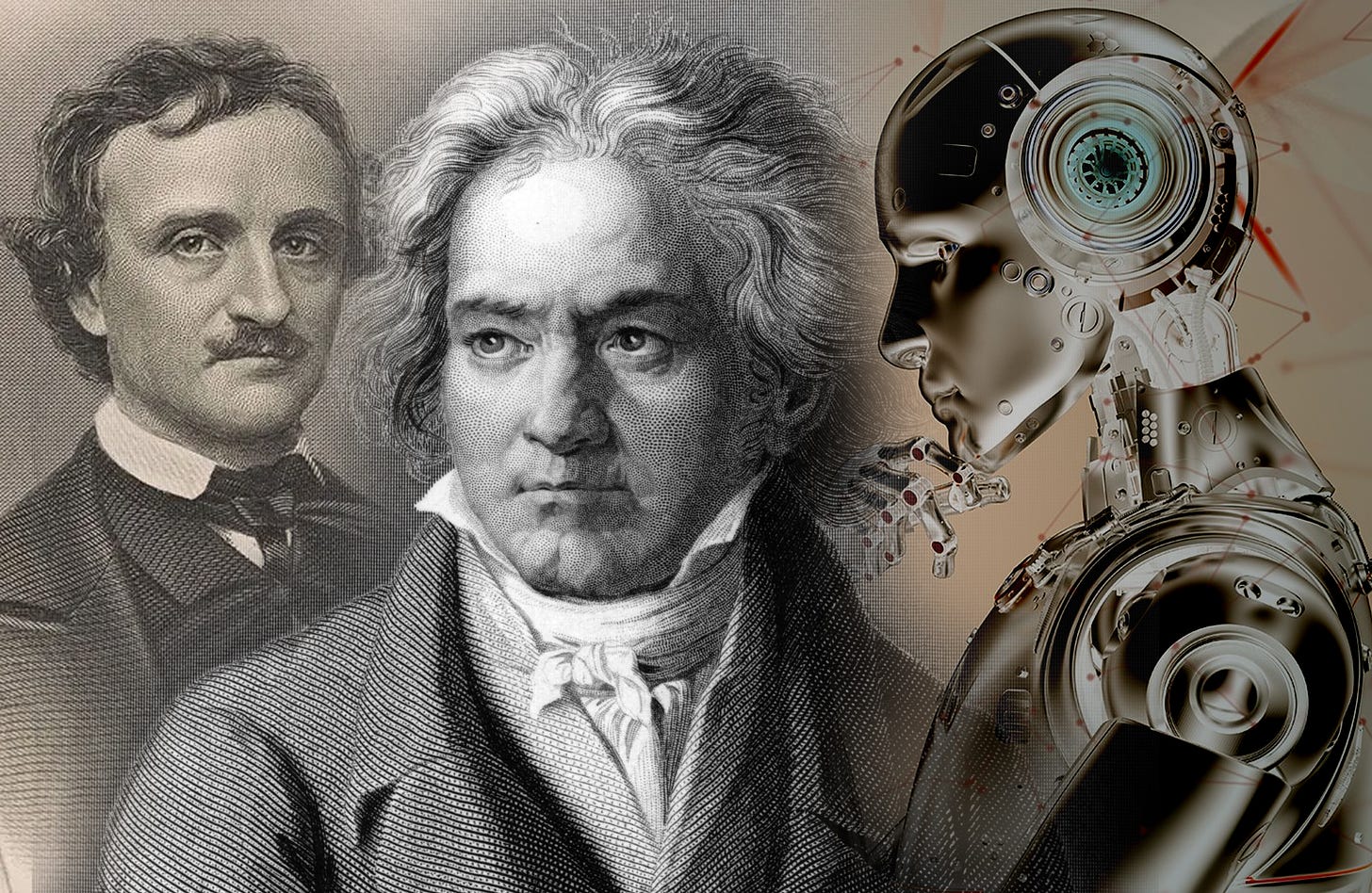

Poe, Beethoven and Houdini VS the Cult of Artificial Intelligence

This is part two of a new series that will develop in tandem with The Occult Tesla series. Click here to read part 1 of the series The Society of the Cincinnatus: Solving a 170 Year Murder Mystery

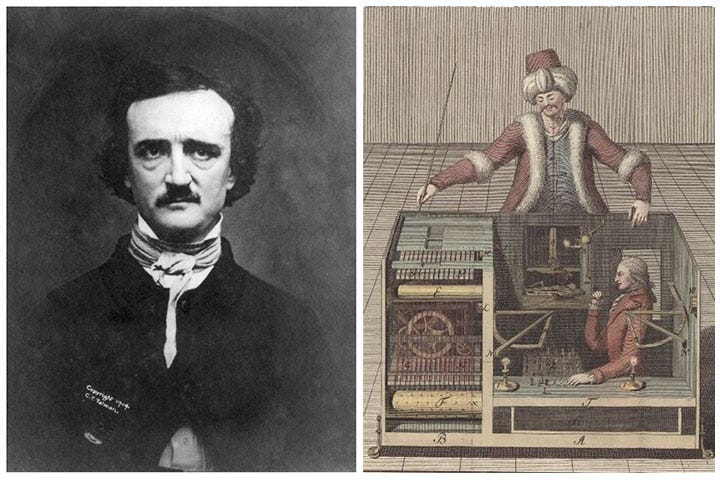

Poe Debunks the Cult of Artificial Intelligence

Throughout his literary works, Edgar Poe not only devoted every effort to expose the plague of irrational spiritualism taking over the American psyche in the mid-19th century, but also demonstrated the tricks of fraudsters that pretended to control “thinking machines” such as seen in Mäelzels's Chess Player, an essay published in April 1836 in the Southern Literary Messenger.

As Allan Salisbury demonstrated in his 1981 pioneering study ‘The Lost Soul of America’, Edgar Allan Poe did much more than simply debunk a travelling hoaxster, but intervened on a much larger psychological warfare operation directed by British intelligence which sought to promote the concept that machines could not only think, but think more effectively than human beings.

Mäelzel’s “Thinking Machines” vs Poe and Beethoven

The ‘automaton’ project was carried out between 1821-1836 by a magician, plagiarist and enemy of Ludwig von Beethoven, named Johann Nepomuk Mäelzel (1772-1838) who toured his chess-playing robot across America convincing millions of Americans of its authenticity. Maelzel’s chess player (dubbed ‘The Chess Playing Turk’ due to the design of the turban wearing robot) was actually not invented by Maelzel, but rather by the earlier Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734-1804). From 1770-1802, von Kempelen toured the device across the courts of Europe where it faced off against royals, Napoleon Bonaparte, Charles Babbage and Benjamin Franklin, winning most matches, and losing some.

Was the machine able to do this by itself? Was there a human agency involved? Some speculated a midget hiding inside the robot, while others speculated that von Kempelen was operating it with magnets. Others still speculated that demonic forces or spirits from another world were animating the machine. Either way von Kempelen enjoyed the ambiguity and never said a word about it.

Although Kempelen’s machine toured Europe for over two decades raising a small fortune, his son didn’t want to continue the family business and sold the device to Johann Maelzel after his father died in 1804.

Music vs Mechanics: Beethoven Steps in

Before launching into his American tour in 1826, Johann Maelzel was most famous as the inventor of the metronome (parodied by Beethoven in an 1817 musical canon), although it has come to be known that he plagiarized the invention from Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel in 1815, added a few insignificant changes and patented it in 1817.

Contrary to popular belief, Beethoven DID NOT believe that metronomes should be universalized or should govern the performance of musical works writing “it is silly stuff; one must feel the tempos”.

The lyrics for Beethoven’s 1817 satirical ‘homage’ is an exercise in sarcastic praise, which modern literalists tend to presume is proof of Beethoven’s adoration for Maelzel:

“Ta ta ta, dear Maelzel

ta ta ta, live well, very well

ta ta ta, you Banner of Time

ta ta ta, you great metronome.

ta ta ta ta ta ta.”

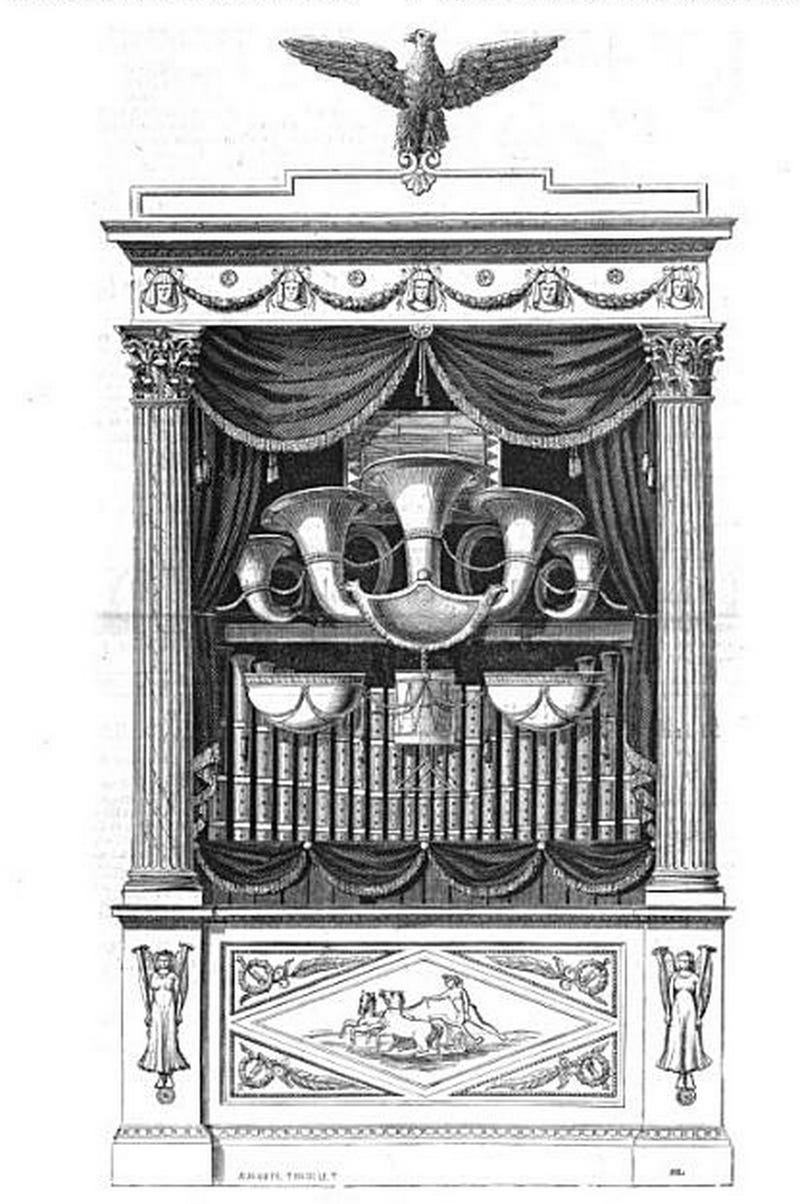

In 1813 Maelzel persuaded Beethoven to compose a symphony that would be played on an automata called the panharmonicon as a fundraiser for the families of German soldiers who were injured fighting Napoleon. This became known as Beethoven’s 8th symphony (sometimes dubbed ‘Wellington Battle’). When the tour began, Beethoven performed his musical score with a full orchestra of human musicians while Maelzel performed a simplified version of the score separately with his panharmonicon automaton, and it was here that a massive controversy arose.

After the fundraising concerts were over, a legal fight broke out with Beethoven accusing Maelzel of stealing his orchestral suit, passing it off as his own, illegally staging performances without the full musical score (which was needed since Beethoven’s music couldn’t be performed by machines). Amidst this quarrel, Beethoven called the Maelzel "a rude, churlish man, entirely devoid of education or cultivation".

In a July 25, 1814 address to artists of London, Beethoven wrote:

“The works that Herr Maelzel performs under the titles of "Wellington's Battle of Vittoria" and "Battle Symphony" are beyond all doubt spurious and mutilated… Herr Maelzel, before he left Vienna, declared that he was in possession of these works, and showed various portions, which, however, as I have already proved, must be counterfeit. The question whether Herr Maelzel be capable of doing me such an injury is best solved by the following fact,--In the public papers he named himself as sole giver of the concert on behalf of our wounded soldiers, whereas my works alone were performed there, and yet he made no allusion whatsoever to me…. I therefore appeal to the London musicians not to permit such a grievous wrong to be done to their fellow-artist by Herr Maelzel's performance of the "Battle of Vittoria" and the "Battle Symphony," and also to prevent the London public being so shamefully imposed upon.” [1]

Contrary to popular belief, Beethoven did not support the idea that Maelzel’s machines, or his mechanical metronome tempos could replace human musicians using artistic intuition and judgement as has been promoted by musicologists since the great composer’s death.

In this author’s assessment, Beethoven’s authorship of the 1913 Battle Symphony was likely done to disprove Maelzel’s claims that machines could replace human musicians and when Maelzel ignored massive components of Beethoven’s scores, and performed the bastardized compositions on his machines without Beethoven’s supervision, the legal proceedings were begun.

Sadly, after Beethoven’s death, much like the case with Poe, his enemies controlled many of the biographies of the musician, painting a vile, arrogant and vindictive personality, while Maelzel has been typically portrayed as an honest victim of Beethoven’s ego. The modern case of the Hollywood film ‘Immortal Beloved’ is merely one recent example of a 250 year tradition of painting Beethoven as a borderline insane irrational recluse.

Fourteen years after Beethoven’s death, a letter was “discovered” and published in his first biography in which the composer appears to have not only fallen in love with Maelzel’s metronome, but has called to universalize its use across Europe while renouncing his use of ‘allegro, adagio and presto’ in writing scores. The 1817 letter associated with Beethoven states:

“So far as I am myself concerned, I have long purposed giving up those inconsistent terms allegro, andante, adagio, and presto; and Maelzel's metronome furnishes us with the best opportunity of doing so. I here pledge myself no longer to make use of them in any of my new compositions. It is another question whether we can by this means attain the necessary universal use of the metronome. I scarcely think we shall! I make no doubt that we shall be loudly proclaimed as despots; but if the cause itself were to derive benefit from this, it would at least be better than to incur the reproach of Feudalism! In our country, where music has become a national requirement, and where the use of the metronome must be enjoined on every village schoolmaster, the best plan would be for Maelzel to endeavor to sell a certain number of metronomes by subscription, at the present higher prices, and as soon as the number covers his expenses, he can sell the metronomes demanded by the national requirements at so cheap a rate, that we may certainly anticipate their universal use and circulation. Of course some persons must take the lead in giving an impetus to the undertaking. You may safely rely on my doing what is in my power, and I shall be glad to hear what post you mean to assign to me in the affair.”

This letter smells of fraud.

IF Beethoven had believed so strongly in the universal application of metronomes to guide all performance as he apparently states in the letter, then why did he only keep this opinion in a private letter which no one saw until 1840? Would he not have yelled it off rooftops and advocated publicly? Also why would he care so much about Maelzel’s business plans in selling the metronomes, even going so far as to commend him in selling the metronomes at higher prices, when it was known by everyone that Maelzel had stolen his device from Winkle?

This would not be the first time that fraudulent letters were forged years after a creative artist died in order to shape a false narrative.

As detailed in part 1 of this series, this is the exact same thing which happened after Edgar Allen Poe died in 1849. Within days Poe’s nemesis Rufus Griswold became his official biographer, became Poe’s literary executor of his estate, purchasing all of his personal letters from the author’s impoverished aunt, and then painting the image of a drunken, death-obsessed, egotistical, opium addict for all posterity. In recent years, it has been revealed that Griswold also forged many letters after Poe had died. [2]

Edgar Poe Debunks Maelzel’s Chess Playing Turk

In his 1836 short tale, Poe proved definitively that Maelzel’s chess-playing automaton was simply a human being hiding inside an elaborate puppet masquerading as a self-thinking machine.

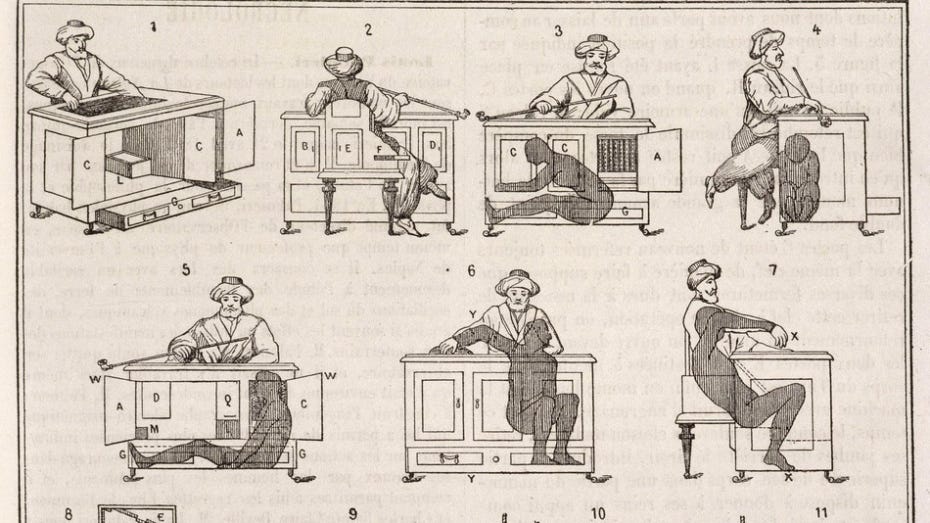

Within his short story, Poe uses basic reasoning skills to determine that Maelzel’s automaton could not be a machine. His points can be summed up in the following observations:

1- The moves of the Turk are not made at regular intervals of time

That is to say, machines utilize a mechanical tempo of some sort which the automata doesn’t follow at all, even though it would be easy for Maelzel to set a time limit for the opponent playing the Turk if he so wished.

2- Agitated motion in shoulder with each move. When the Automaton is about to move a piece, a distinct motion is observable just beneath the left shoulder, and which motion agitates in a slight degree

3- The Automaton does not invariably win the game.

Poe here makes the point that since machines follow perfect mathematical logic (as does chess in an ideal state) it makes no sense why the machine would sometimes loose matches

4- Mirrors appear to be positioned within the machine’s interior in order to fool spectators into believing that there is much more complexity inside the device while obscuring the fact that space exists for an adult chess player to move freely within it.

5- The external appearance, and especially, the deportment of the Turk, are un-necessarily rigid despite the fact that Von Kempelen made many machines (which Maelzel had toured with) that were much more lifelike. Since incompetence was not the reason for the rigidity, it must have been caused by design.

6- Winding up inconsistency. Before each game, the machine is wound up, and yet no spring exists that could account for the length of time which the machine has been known to play for. Additionally, Poe notes that it was observed that the machine was not wound sufficiently to account for the long play times.

7- That the Turk is significantly larger than a normal human being and would easily fit a human chess player within it

8- The internal walls of the machine un-necessarily lined with cloth, which would serve “to deaden and render indistinct all sounds occasioned by the movements of the person within.”

9- The antagonist in the audience is not permitted to come close to the machine while playing. Poe speculates that if Maelzel were to allow this, then he risks the antagonist hearing sounds of the human within the machine.

10- When disclosing the interior to the audience by opening up the three cupboards, Maelzel always follows a similar pattern.

Poe writes: “For example, he has been known to open, first of all, the drawer — but he never opens the main compartment without first closing the back door of cupboard No. 1 — he never opens the main compartment without first pulling out the drawer — he never shuts the drawer without first shutting the main compartment — he never opens the back door of cupboard No. 1 while the main compartment is open- and the game of chess is never commenced until the whole machine is closed.”

11- Maelzel’s assistant is never visible when the machine is active.

Poe writes: “While the Chess-Player was in possession of Baron Kempelen, it was more than once observed, first, that an Italian in the suite of the Baron was never visible during the playing of a game at chess by the Turk, and secondly, that the Italian being taken seriously ill, the exhibition was suspended until his recovery… Similar observations have been made since the Automaton has been purchased by Maelzel. There is a man, Schlumberger, who attends him wherever he goes, but who has no ostensible occupation other than that of assisting in the packing and unpacking of the automata. This man is about the medium size, and has a remarkable stoop in the shoulders. Whether he professes to play chess or not, we are not informed. It is quite certain, however, that he is never to be seen during the exhibition of the Chess-Player, although frequently visible just before and just after the exhibition.”

Maelzel’s efforts to convince Americans that humans would inevitably be replaced by machines (using mathematical logic as the sole definition of “thinking” permitted) was again picked up by Thomas Huxley and Nikola Tesla decades after Poe had died (elaborated in part 7 and part 9 of this series).

Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin Exposed by Harry Houdini

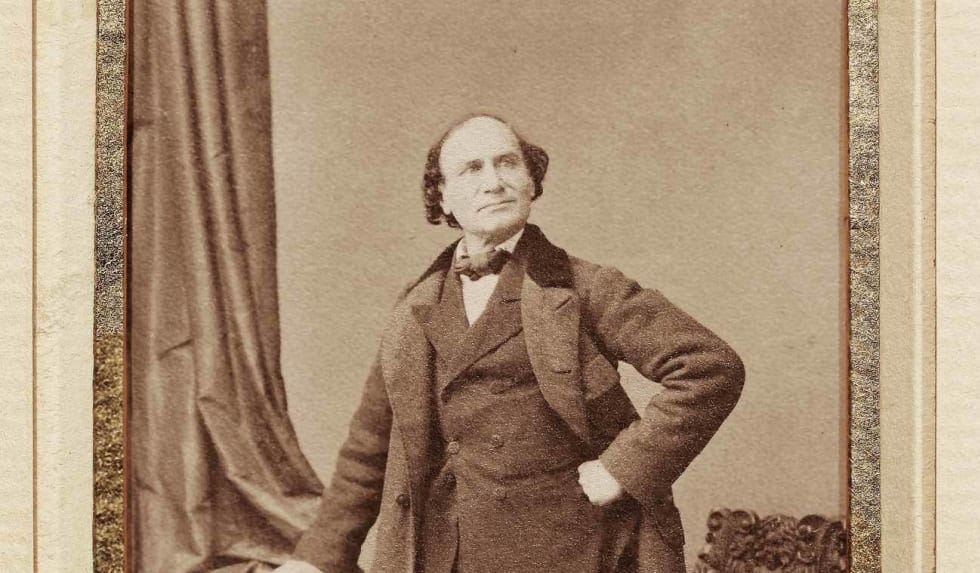

After Poe’s death, the rise of the automata project was taken up by french magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871), who not only claimed to have invented several types of automata himself (including several which answered a diverse array of questions from the audience) but also the trick of ‘second sight’ and levitation.

Robert-Houdin received bountiful support from King Louis-Philipe in France starting in 1847 who helped him create the largest magic show in Europe at the Palais Royale. After the revolution of 1848, Robert-Houdin was invited to England where he performed for Queen Victoria and leading members of the British elite.

When Napoleon III consolidated control of France, and established a new Anglo-French alliance for world empire, Robert-Houdin was invited back to Paris where he became a magician for the empire, where he was sent to perform magic in Algeria to convince the various tribal chieftains that French magic was more powerful than Islamic magic used by Marabout leaders of the revolts. Robert-Houdin’s success at subverting the Algerian uprisings of 1858 was rewarded handsomely by Napoleon III.

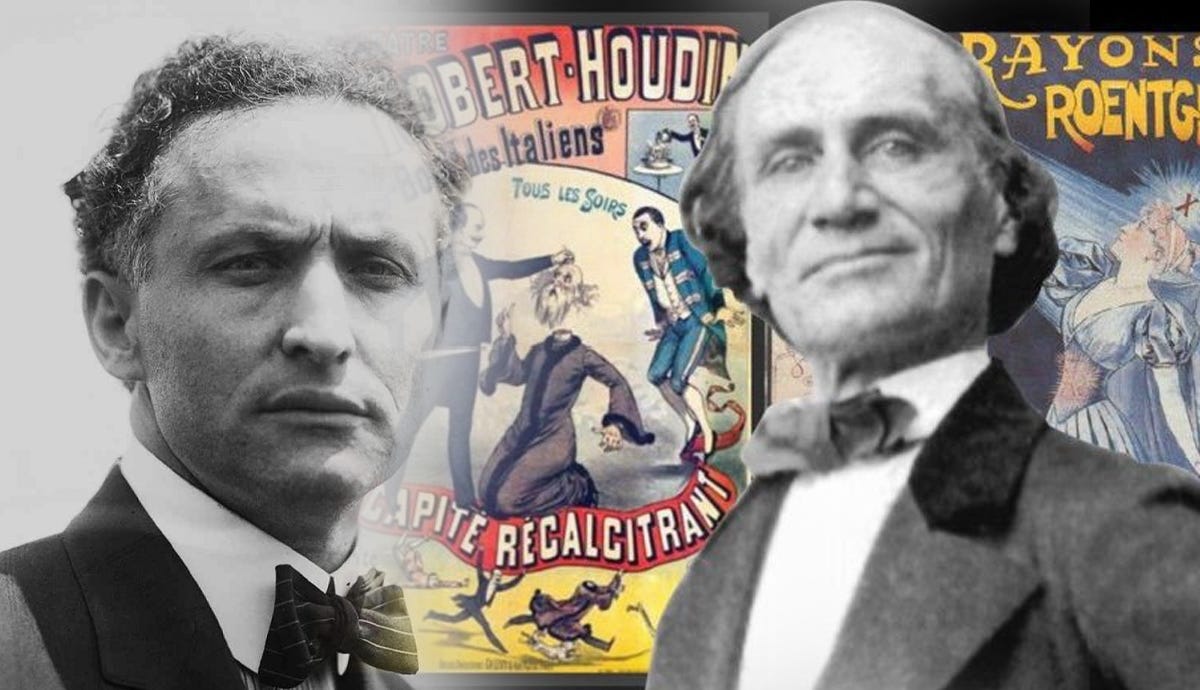

As a young man, Harry Houdini had originally been inspired to enter the field of magic after reading the memoires of Robert-Houdin, even adopting the name ‘Houdini’ as an homage to his hero.

However upon discovering that his hero was a plagiarist and a fraud, took a page from Poe’s ‘Maelzel’s Chess Player’ and wrote a book called ‘The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin’ in 1907 documenting the origins of the tricks which Robert-Houdin claimed as his own.

Houdini began his expose writing:

“His fame, which has been sung by writers of magic without number since his death, rests principally on the invention of second sight, suspension, and the writing and drawing automaton. It is my intention to trace the true history of each of these tricks and of all others to which he laid claim as inventor, and show just how small a proportion of the credit was due to Robert-Houdin and how much he owed to magicians who preceded him and whose brain-work he claimed as his own.”

Throughout this controversial book, Harry Houdini demonstrates that the automata which Robert-Houdin claimed to have invented and also claimed could answer elaborate questions posed by audience members were stolen from real inventors that lived decades prior to Robert-Houdin. Houdini rigorously demonstrates how Robert-Houdin employed the use of electrical wires, and like Maelzel earlier, used human controllers manipulating the elaborate devices to give off the false impression that they were thinking for themselves.

Houdini also demonstrated that electric wires, and elaborate code systems were integral to Robert-Houdin’s use of ‘Second Sight’.

As outlined in part 11 of The Occult Tesla, we reviewed not only how Harry Houdini’s war against the fraudulent spiritualists subverted the creation of a world gnostic religion, but also how the attraction and power of the leading spiritualists, channelers, theosophists, and modern wizards relied heavily on 1) a superstitious population addicted to belief in sense impressions and 2) illusionist trickery developed by stage magicians like Johann Maelzel and Robert Houdin.

Thomas Huxley and Tesla Revive the Human Automata Project

A mere three years after Robert-Houdin’s death, the ‘Human Automata project was revived in 1874 through Thomas Huxley’s famous Royal Society lecture ‘On the Hypothesis that Animals Are Automata’.

In this famous speech, Huxley called for scientific demonstrations to be created that would advance his thesis that:“No evidence can be found for supposing that any state of consciousness is the cause of change in the motion of matter of the organism. . . . The mind stands relegated to the body as the bell of the clock to the works, and consciousness answers to the sound which the bell gives out when it is struck.”

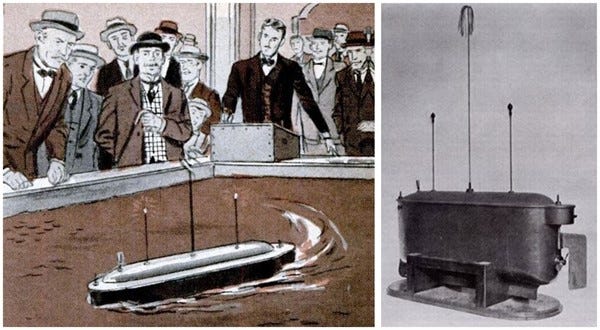

It was Huxley’s own self-identified automaton named Nikola Tesla who toured the USA from 1898-1900 showcasing his Telautomata which supposedly answered any mathematical question the audience asked.

Instead of revealing the radio signals controlling his device animated by a human assistant outside the view of the audience, Tesla instead evoked the spirit of Johann Maelzel by invoking the belief that he was controlling it through his mind when he stated;

“By an effort of will… I can stand two meters away from that instrument and by a mere stiffening of my muscles cause it to send a signal. It is so delicate in its adjustment that the disturbance of the electrical equilibrium caused by my muscular action affects it.”

After Tesla’s project failed to win over the population, the automata project was amplified once more with Alan Turing, Norbert Wiener and John von Neumann in the wake of World War 2. These figures played the role of pioneers of the emergent cult of Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism and Cybernetics.

In the next installment of this series, we will be introduced to Poe’s Tales of Ratiocination and the character of Inspector C. Auguste Dupin.

Footnotes

[1] Beethoven’s Letters, Volume 1, Entry 127 — Beethoven’s depositions in court against Maelzel’s fraud additionally point to Maelzel’s influence among the controlling editors of newspapers of Vienna, as Beethoven says: “I sent what follows to a newspaper, but the editor would not insert it, as Maelzel stands well with them all.”

[2] To fully appreciate his disdain for Poe, it is worth reading his published eulogy a day after Poe died (October 8, 1849) where Grisworld wrote: “Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it… There seemed to him no moral susceptibility. And what was more remarkable in a proud nature, little or nothing of the true point of honor. He had, to a morbid excess, that desire to rise which is vulgarly called ambition, but no wish for the esteem or the love of his species, only the hard wish to succeed, not shine, not serve, but succeed, that he might have the right to despise a world which galled his self-conceit.”

Great piece to show the hidden part of history. Especially the Cincinnati Society was unknown to me.

Mindblown! It would be awesome one day to make a graph with evry inventor or influencial genius of the past, one side forthe legit, one side for the fake one. If i try the exercise i will certainly ask you for guidance. I guess if we start by putting the real genius on one side it will be waaay faster. 😆