Why Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Despised Edgar Allan Poe

Forty years after Edgar Allan Poe’s murder, Dr. Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (initiate of the United Grand Lodge of England, Order of the Golden Dawn, and Edinburg surgeon) created a character named Sherlock Holmes who made his first appearance in the 1887 novel ‘A Study in Scarlet’.

In Doyle’s 56 stories featuring Sherlock Holmes written between 1887-1930, the fictional detective is featured as a cocain-addicted logician whose inductive-based leaps into solution concepts to crimes were pure mysticism devoid of actual use of human reason.

The strange scenario of Doyle’s first appearance of Sherlock Holmes in the 1887 ‘A Study in Scarlet’ is extremely interesting as it features the story of a serial murderer who is gaining revenge on leading Salt Lake City Mormons travelling in England who had murdered his lover years earlier.

Three important clues surround Doyle’s creation of Sherlock Holmes:

1) Doyle’s 1887 initiation into English Freemasonry’s Phoenix Lodge No. 257 in Portsmouth.

2) The 1888 Jack the Ripper murders which Doyle’s mentor (and model for the character of Holmes) participated in investigating with Scotland Yard.

3) The location which Doyle chooses to give to his fictional character’s residence one full year before the Jack the Ripper murders begin.

Despite professing to be an admirer of Edgar Allan Poe, claiming to have gained inspiration from Poe’s character C. Auguste Dupin (the main character of Poe’s tales of ratiocination), Sir Arthur Conan Doyle began his very first Holmes tale by denigrating Poe directly, as his detective responds to Watson’s foolish comparison of Sherlock’s analytical powers and those of Poe’s Dupin.

“No doubt you think that you are complimenting me in comparing me to Dupin,” he [Sherlock] observed. “Now, in my opinion, Dupin was a very inferior fellow. That trick of his of breaking in on his friends’ thoughts with an a propos remark after a quarter of an hour’s silence is really very showy and superficial. He had some analytical genius, no doubt; but he was by no means such a phenomenon as Poe appeared to imagine.”

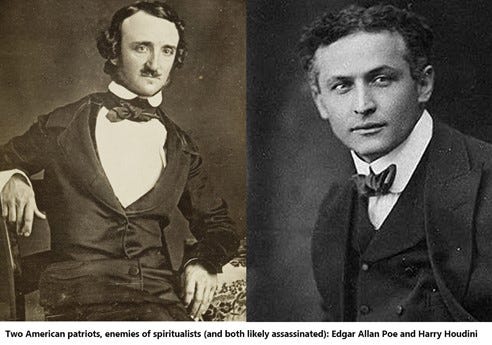

It has recently come to light that Harry Houdini, a living nemesis of Doyle, took inspiration from Edgar Poe, modelled his method of thinking on Poe's inspector and did his own research on Poe’s own writing desk which Houdini purchased in 1924.

Houdini had even accused Sir Doyle of plagiarizing Poe’s Purloined letter in crafting the first short story featuring Sherlock Holmes (in the 1891 A Scandal in Bohemia). Houdini wasn’t alone in these observations, as Sidney Teiser noted in his famous 1903 NY Times article, Doyle’s Adventures of the Speckled Band (1892) was lifted from Poe’s Tell Tale Heart (1843) and researcher Stephen Bergman more recently noted that Doyle’s Sign of Four (1890) plagiarized Poe’ Murders on the Rue Morgue (1841).

Since Doyle would frequently use his persona of ‘Sherlock Holmes’ when carrying out cover-ups of crimes on behalf of the spiritualist movement in London and the USA (as outlined in part 11 of The Occult Tesla), it is worth investigating what Doyle’s “fictional character” truly represented.

In opposition to the type of healthy reasoning skills expressed by Poe and his character Dupin, Doyle’s fictional sleuth expressed a religious-like disdain for any truth that fell outside of “practicality”.

This disdain for Poe’s method of thinking, and his embrace of deductive/inductive thinking fused with mysticism and drugs was outlined in Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet (1887) when Sherlock’s assistant Watson presents the great detective with evidence of the heliocentricity of the solar system. Holmes immediately responds with:

“Now that I do know it I shall do my best to forget it.”

“To forget it!”

“You see,” he [Holmes] explained, “I consider that a man’s brain is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across so that the knowl- edge which might be useful to him gets crowded out, or at best is jumbled up with a lot of other things, so that he has a difficulty in laying his hands upon it. Now, the skillful workman is very careful indeed as to what he takes into his brain-attic. He will have nothing but the tools which may help him in doing his work, but of these he has a large assortment, and all in the most perfect order. It is a mistake to think that that little room has elastic walls and can distend to any extent. Depend upon it, there comes a time when for every addition of knowledge you forget something that you knew before. It is of the highest importance, therefore, not to have useless facts elbowing out the useful ones.”

“But the solar system!” I protested.

“What the deuce is it to me?” he interrupted impatiently; “you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work.”

A Mystical Drug Addict

Although many a fan would hate to admit it, Sherlock’s super-human powers of deduction were entirely based upon the character’s relationship with drugs (ranging from opium to cocaine)… which served as spinach to Sherlock’s Popeye.

Describing Sherlock’s drug addiction, Doyle writes:

“Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantle-piece and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long, white, nervous fingers he adjusted the delicate needle and rolled back his left shirt-cuff. For some little time his eyes rested thoghtfully upon the sinewy forearm and wrist, all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks. Finally, he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined armchair with a long sigh of satisfaction.”

After having been portrayed as the most pre-eminent thinker, problem solver and renaissance man of his age, it becomes clear that the character of Sherlock Holmes not only has managed to become the most powerful, knowledgable man alive, and yet have no control over himself. Even moreso, Holmes even seeks to encourage his new assistant Watson to join in his hellish addiction. In the chapter of ‘A Study in Scarlet titled ‘The Science of Deduction’, Watson asks his mentor:

“Which is it today,’ I asked, ‘morphine or cocaine?’

He raised his eyes languidly from the old black-leather volume which he had opened.

’It is cocaine.’ he said, ‘a seven percent solution. Would you care to try it?”

After Watson declines, Holmes justifies his addiction (supposedly representing the caricaturesque image of Edgar Poe) by saying:

“I suppose that its influence is physically a bad one. I find it however, so transcendentally stimulating and clarifying to the mind that it's secondary action is a matter of small moment.”

Holmes continued:

“My mind… rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram, or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants. But I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation.”

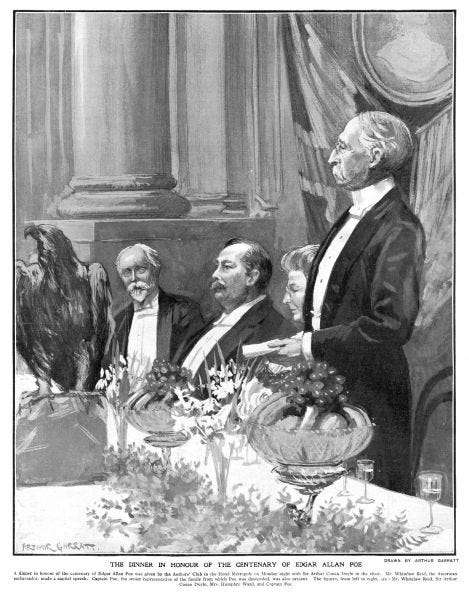

Sadly, due to the success of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Doyle quickly became treated as an authority of Edgar Poe and spoke at Poe memorial commemorations for years, as the imperial poet continued weaving false profiles of the slandered Poe.

In an 1909 memorial ceremony held in New York, Doyle delivers strange praise to Poe’s “masterful and original” works by stating them to be “so devoid of message, that one feels their limitation.”

After outlining the death of Poe’s young wife, Doyle described the poet as “a broken and desperate man”, and always while praising Poe’s asked rhetorically: “Is it a wonder that it left him a broken thing, a man without hope or purpose in life, a husk from which the virtue and energy had been taken?”

Poe’s Stance on Drugs

We have already discussed in episode one of this series, how Poe’s living nemesis Rufus Griswold took control of Poe’s memory upon the great poet’s death, and painted a false image of Edgar Poe as a debauched opium addict with an obsession for death and morbidity.

Not only did Griswold (who also controlled the narratives of the life of Poe’s ally James Fenimore Cooper) lie profusely, projecting his own malevolent drive into the personality of the late Poe, but forged letters in Poe’s name while destroying countless other writings by Poe acting as executor of his literary estate. Despite the fact that Griswold’s profile of Poe was debunked numerous times over the last century, Poe’s image of a drug addict obsessed with death painted by Griswold is still dominant in the mass psyche.

While Conan Doyle’s many “homages” to Poe admittedly denied certain excesses of Griswold’s characterizations, his own embrace of drugs perhaps had something to do with his willingness to associate genius with insanity.

As Drs. Daniel and Eugene Friedman demonstrate in The Strange case of Dr. Doyle: A Journey into Madness and Mayhem, Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was himself a prolific user of a variety of drugs from his days as a medical student who self-experimented with opiates until his later years as the overseer of a new world religion of fairie queens, and spiritualism. Thus his own portrayal of Sherlock Holmes’s drug use could be said to partake in a fair bit of autobiography.

As we will see in future installments of this series, Poe’s relationship with opium and even alcohol was very different from that of Doyle’s, and although the drug features prominently within many of Poe’s tales and poems, it was never portrayed as a cause of genius, but always as a cause of insanity and self-destruction. This includes his stories The Duc de l’Omelette, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, The Cask of Amontillado, The Mask of the Red Death, the Fall of the House of Usher, Life in Death, The Black Cat, Ligeia and Berenice.

The reader has two choices when confronting those famous writings by Poe outlined above.

The first choice which falls into the choice made by Griswold, Doyle or the majority of today’s “Poe scholars” presumes that Edgar Poe’s self-destructive characters were simply Freudian calls for help or perhaps, Poe’s own morbid efforts to admit his own fiendish vices in some effort to self-destruct the way his characters had done.

The second, less popular, but correct choice is to recognize the presence of an insightful mind who both understood the structure of evil, and how to defeat it.

These were lessons for which Poe’s rosicrucian enemies (including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) would never forgive him.

I almost fell out of my chair when you mentioned your suspicions about Doyle and the Ripper murders because I had just put together associations on my India graph that made me suspect that the Theosophists were involved. They and those around them were responsible for the fractalization of theories soaked up by the public. That's early Mindwar stuff.

I am now curious as to whether a careful reading of Sherlock Holmes might reveal crimes of the Theosophists.

Your tribute to Poe, and Houdini as well, in this series trumps the obfuscation long endured by these disguised “writers of history”. Thanks and God Bless!??